“How Science and Genetics are Reshaping the Race Debate of the 21st Century.” Author Vivian Chou brings up a fascinating point in this article, where they explore the effects of Donald Trump’s election as the 45th President of the United States and the subsequent racial conflicts that followed.

But first, the science. In 2003, the Human Genome Project was completed, enabling the connection between human ancestry and genetics to be explored. The main way the public has been able to explore this connection is through ancestry test kits such as 23andMe, Ancestry, and Family Tree DNA; family ancestry has now been made affordable, at the price of $99. These ancestry test kits sort ancestry into 5 racial categories: Africa, European, Asian, Oceania, and Native American, with the belief that our DNA can tell us how much we belong into each category — with the precision of a percentage.

Truthfully, racial identity isn’t that simple. Human populations do group together in certain geographical regions, but the genetic variation between regions in small, and there is no uniform identity that can be found in each individual in that region. In this way, the estimations of at-home ancestry test kits — which estimate racial identity do to 0.1% — aren’t entirely accurate. One testament as to why this is can be found in a 2002 Stanford study, where scientists looked for diversity across the 7 major geographical regions of 4,000 alleles. The study found 92% of alleles were present in two or more regions, and almost half the alleles studied were found in all 7 regions. It concluded that all humans on the planet are fundamentally similar — a conclusion that many other scientists have drawn in the past after doing similar studies.

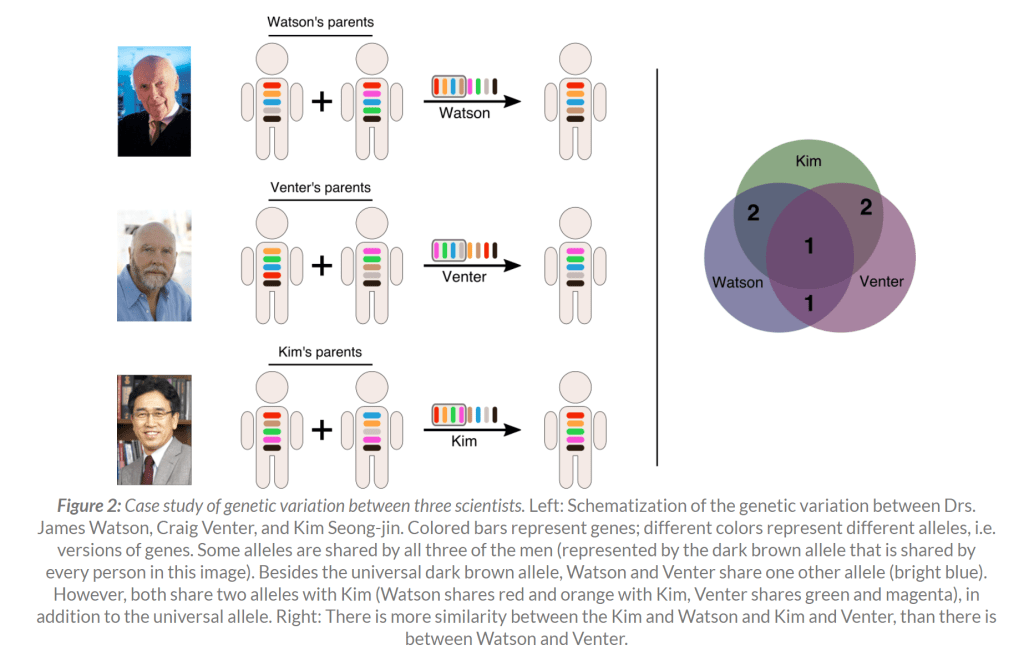

To determine whether racial/ethnic groups truly existed within human DNA, the scientists expected to find “trademark” alleles that were specific to a certain racial group, but not found in any others. The study found that 7.4% of the 4,000 alleles were specific to one geographical region, but that when those region-specific alleles were present, they could only be found in about 1% of the population. As a result, the scientists concluded that the construct we call “race” has no distinct genetic markers separating it from the rest of the human population. One example of this conclusion is evident in a diagram from the article:

The diagram shows how Kim is more genetically similar to Watson and Venter than Watson and Venter are to each other, even though physically one notices that Watson and Venter look more alike. In this way, this diagram demonstrates how race is much more a social construct, rather than a scientific one. As a result, scientists today prefer to use the term “ancestry” rather than “race” to describe human diversity — because the term “ancestry” acknowledges the relationship between humans and the geographical locations their ancestors lived in, but it doesn’t put humans into a specific category like the term “race” does.

Humans share 99.9% of our DNA with each other — that, is a widely known fact. However, it doesn’t seem to mean anything to the social construct of race; humans generally seem to disregard it as they are considering the value of race, in order to maintain the integrity of the construct. Because, if we acknowledged that even though physically, we may seem different, that there is in fact miniscule genetic variation between us, wouldn’t that undermine the construct that society has been formed around for the past couple centuries? Wouldn’t it disprove all of the thinking of multiple scientists, the idea of social Darwinism, and bring the harsh cruelty that has been a result of atrocities committed due to race to light, without a justification? The answer is yes — and should you find yourself wanting to learn more, the article provides a clear example: the actions and beliefs of the alt-right movement.

Now what? We’ve just learned — more likely, reviewed — the idea that race really has little tie to genetics. It is much more, if not entirely, a social construct than a scientific study. I had a hunch that this would be the conclusion, but I was still curious, because I was skeptical as to how race could remain so firmly ingrained in our society even though science has essentially disproved any ideas on an individual’s cleverness, or any other characteristic, that the idea of social Darwinism brings to race.

My takeaway is increased awareness. The article reads that race has persisted in society because people have either not had the access to, or been able to ignore, scientific findings on race. To counteract that, Vivian Chou suggests people must dissuade misinterpretations and/or ignorance of these scientific findings — the idea being, if people educate themselves on the science, and really understand how the studies they are reading are true, then race as a social construct will gradually be able to dissolve.